Kaleem Omar: The literary legacy of Pakistan's most influential poet and journalist who shaped English poetry

JournalismPakistan.com |

Published last month | Dr. Nauman Niaz (TI)

Join our WhatsApp channel

ISLAMABAD— It was the late Colonel Mushtaq Madni, himself a familiar presence upon the Editorial pages, who first ushered me into the sanctum of The News. We entered the Resident Editor's room, a chamber perfumed with the somberness of print, and there he sat, Kaleem Omar. The man I had long known only through bylines and the weight of words revealed himself now in flesh: a figure somewhat corpulent, his hair already flecked with the autumnal greys, a moustache measured and sufficient, his attire no more than a loosely worn shalwar suit.

How inadequate the contrast between the outward simplicity of the man and the splendour of his prose! In the newspapers, his sentences flowed with poetic ease, compelling the reader to surrender, to drift upon a surge of imagery and metaphor, carried along by a vocabulary at once rich and precise. There was in his writing not just polish, but a touch of rare grace, absolute class, I thought, the sort which cannot be taught nor imitated, but must be born within. And now, meeting him in person, I found myself struck dumb: by the gentleness of his manner, the affectionate cadence of his speech, and the unforced depth of his literary discourse. It was an occasion, an encounter one marks inwardly with reverence, the kind one stores in the memory for later recall, like the opening of a great symphony.

Colonel Madni, ever the courteous intermediary, made the introduction, telling him of my young passion for literature and philosophy, of my quest for first editions as others might quest for treasure. Omar listened and smiled, a smile at once indulgent and paternal. 'You are too young,' he said, 'to be consumed by the world of literature. Enjoy! Be a free bird, and fly while the wings are strong. Do not curtail your youth; do not resign it to the cage of solemn libraries. Let the air of freedom be your companion.'

Yet, perceiving the stubborn earnestness of my interest, he relented, and with that gentle authority which was his hallmark, directed me towards the novels of William Makepeace Thackeray and the sweeping canvases of Honoré de Balzac. His conversation with Colonel Madni soon turned to David Hume, and I listened, transfixed. The ease with which he traced the arguments of the philosopher, the way his voice coloured abstraction with human meaning, was nothing short of astonishing.

Thus was my first meeting with Kaleem Omar: an initiation not just into the presence of a man, but into the atmosphere of letters, philosophy, and art that seemed to surround him like an invisible aura. It was not a dialogue so much as an overture, a prelude to the recognition that in him dwelt the soul of a true man of letters, unpretentious yet profound, generous yet exacting, worldly yet touched always with the cadence of poetry.

Early Life: From Lucknow's Literary Heritage to Pakistan's New Dawn

He was born in 1937, in Lucknow, a city already laden with palimpsests of memory, where every alley hummed with Urdu couplets echoing against weathered walls, and every courtyard still breathed faintly of the nawabs' vanished grace. It was from this city, steeped in antiquity, that Kaleem Omar began his journey. Sherwood College in Nainital polished his early years, but destiny soon reclaimed him for the newly cut cloth of Pakistan. From the very outset, one senses in his life the turbulence of change, the tremor of shifting borders, the ache of dislocation.

Kaleem Omar was born into an older world, yet within him lived the unquiet stirrings of the modern. A poet and a journalist, a wanderer and a witness, he carried in his spirit both nostalgia and critique. His life was composed of many niches: son of a prosperous business family, Omar Sons, once thriving in East Pakistan; a scholar shaped in colonial classrooms; a traveller to England; and, finally, a returnee, his vision sharpened by exile. But his exile was not simply geographic; it was emotional, historical, and existential. His was the displacement of memory, the estrangement of one who carries within him fragments of a world dismantled. This condition, this yearning for what had been lost, became the leitmotif of his poetry and prose.

The Journalist's Calling: Mastering the Art of Words

His entry into journalism was less a career than a calling. The newspaper offices received him as one of their own, and soon his columns unfurled with a mastery rare in any age. With swift, mercurial turns, he would pass from politics to sport, from film reviews to searing investigations. His style carried the hallmark of precision yet never denied itself wit, its joy in the overlooked detail, its affection for the image almost discarded by others. To read Kaleem Omar was to be guided through the labyrinth of history while still hearing the mischief of the present.

In the drawing rooms of Karachi and Lahore, he became a familiar figure: the shalwar-kameez and waistcoat worn lightly, books tucked beneath his arm, his eyes carrying both mischief and melancholy. He quoted Eliot, Pound, and Auden, not as pedantry, but as if they were companions at the table, voices in the ongoing colloquy of life. He admired them, yes, but he was never their mimic. For in the fragile yet luminous space of Pakistani English poetry, his was an authentic voice.

Building Pakistani English Poetry: The Wordfall Generation

There, among peers such as Taufiq Rafat, Maki Kureishi, and Zulfikar Ghose, he helped shape a new tongue for a new land. His role in Wordfall, the 1975 anthology he co-edited with Rafat and Kureishi, was a landmark in itself: a gathering of voices still tentative, yet essential in their music. Within its pages, his own poems glimmered. Satirical and sharp was It Didn't Really Happen, political in its bite, mordant in its humour. And then came Trout, with its sensuous evocation of riverbanks, the gleam of spoons, the small, innocent rituals of the day, poetry that bridged private memory and collective resonance, at once luminous and immediate.

Poetry of Loss and Memory: Understanding Endonostalgia

Loss shadowed him always. The early death of his father left an emptiness into which his verse would continually return. The dismemberment of East Pakistan toppled the family business and scattered certainties like autumn leaves. Friends departed, ideals frayed, the certitudes of youth dissolved into the dim ache of remembrance. These were not simply episodes of biography; they were the very soil from which his poems grew. His art does not soothe so much as reveal: nostalgia not for a golden triumph, but for absences, for lives no longer lived, for futures unfulfilled. Critics later called it endonostalgia, a longing not for places never seen, but for one's own lived past, now lost to time. In Kaleem Omar's lines, this endonostalgia found one of its truest expressions.

Consider his Poem for My Father:

I remember how we would sit quietly, hour after hour,

and listen to your plans.

Here, the small moment expands until it illuminates an entire life, its tenderness folded delicately into time's cauldron. Yet irony never lay far from him. He was the journalist who updated his own obituary each year, who joked about his standing on Google searches, who carried within him both sobriety and play. His appetite for the trivial was as sharp as his instinct for the momentous.

The Unfinished Masterpiece: A Troubadour's Life

He left behind an unfinished opus, A Troubadour's Life, three hundred segments of a poem that might have been his grand testament. In that incompletion lies something symbolic: Kaleem Omar's life itself remained unfinished, open, restless, seeking. He was always mid-sentence, always between the elegiac and the satirical, between the historian and the dreamer.

Such was Kaleem Omar: a man of Lucknow and Nainital, of Karachi and Dhaka, of England and exile. A poet who knew that memory itself is a country, fragile and uncharted; a journalist who reminded us that the present cannot be divorced from the long shadow of the past. In his words, Pakistan heard itself, its dismemberments, its yearnings, its small joys by a river's edge, its silences in the night.

And in that hearing, the man himself endures, as all true poets endure: not only as a raconteur of what has passed, but as a voice still resounding, lyrical, elegiac, and wholly alive.

The Man Behind the Words: KO's Daily Life

His humour was large, like his presence. To friends, he was simply 'KO,' rough-hewn at the edges, forever cradling a cup of chai, delighting in banter, in the latest political scandal or yesterday's cricket score, yet always with a poet's somberness, a seriousness that underlay the play. He lived among yellowed newspapers and the smoke of ceaseless cigarettes, amid the hammering of typewriter keys. He was never a recluse; rather, a vivid presence. One encountered him everywhere: in literary gatherings where words swirled like incense; at dinners alive with argument; in the cacophony of newsrooms; or simply in silence, observing the world with that half-quizzical, half-melancholic gaze.

Literary Mastery Across Media: From Politics to Poetry

As a journalist, he was protean. His columns appeared in English, The Star, The News International, and beyond, moving across politics, society, sport, and film with a fluency few could rival. His writing bore the weight of fact, the rigour of reportage, but beneath it ran the finesse of poetry. He sought never the plain tale but the turn of phrase, the evocative gesture, the telling detail that reveals not only what happened, but what it meant.

One recalls him vividly in Lahore's restaurants or Lucknow's old libraries: a slim young man with mop-top hair, books piled around him like fortresses, his eyes alive in candlelit arguments. Amid the many voices and clamorous opinions, his own remained constant, generous with trivia, abundant with allusion. He quoted Eliot or Auden as naturally as breath, yet in the next instant would recall the cadences of Urdu masters or local mentors. Above all, he spoke with reverence of Taufiq Rafat: friend, guide, midwife to his poetic voice. That mentorship was not symbolic only; it shaped the very rhythm of his verse—the pauses, the hesitations, the silences as important as the speech.

The Dual Nature of Omar's Poetry: Joy and Lament

His poetry carries the dual inheritance of delight and lament. In Trout, that shimmering evocation of riverbanks, spoons, dawn-light, and the innocent rituals of small hands, one tastes both joy and the ache of impermanence. Daily things gleam, yet even as they are celebrated, they seem already slipping away. In Hunters in the Snow and other poems, the metaphors deepen: the cold, the distance, the glittering harshness of snow—yet within that frost glows life's strange, severe beauty.

The Final Chapter: Death and Immediate Legacy

Death came, as it must, on 25 or 26 June 2009 (accounts vary), of heart failure in Karachi. He was 72, more or less. The morning's newspapers carried the announcement, and with it the sense that an era had closed. For a voice that seemed to embody endurance, that seemed imperishable, had fallen silent. He left behind a treasury, poems, columns, memories, and, most heartbreakingly, fragments of his unfinished epic, A Troubadour's Life: a love-song to his own wandering existence, left suspended in the air.

Yet silence was never his fate. In the obituaries, in anecdotes retold, he remained: his "bhai, chai pilao"; the clatter of his keys; the clouds of smoke curling like punctuation in a newsroom; his fondness for images both dramatic and ordinary. Piece by Piece of My Life, Dawn's tribute, evoked a man who never wearied of living, whose pursuit of words was itself a form of breathing.

Building Pakistani Literary Tradition: From Mimicry to Innovation

His legacy belongs to the lineage of those who made Pakistani English poetry not an act of mimicry but one of invention. He took foreign metres, alien cadences, and filled them with the air of the subcontinent: with soil and fruit, grief and longing, politics and passion. His name stands among the builders of tradition, who transmuted experiment into inheritance.

Family Connections and Personal Struggles

But he was not only a poet and columnist; he was family too, cousin to Irfan Husain, Ahmed Rashid, Zeenat Ziad. Yet always he walked his own path, uneasy with privilege, haunted by memory, restless in exile, inhabiting the fissure between private loss and public duty. His private life bled into his public one: the dinner-table conversation as rich as the column; the personal regret folded into the public critique.

The Troubadour's Eternal Journey: A Life in Motion

In truth, his life was indeed that of a troubadour: wandering with poems in his pocket, with columns in the morning press, with Lucknow's dust still on his shoes, Lahore's books still under his arm, Karachi's sea-wind in his lungs. He lived between longing and critique, between elegy and satire. That the final great poem remained unfinished seems apt: his life itself was always in progress, perpetually incomplete, seeking, yearning.

The Voice That Endures: Omar's Literary Philosophy

What endures is the voice. Robust, lyrical, tinged with wit, perpetually remembering. The small gestures, a mentor's name recalled, a book pressed into another's hand, a lament spoken softly at a friend's death, a dawn celebrated in print. And the larger ones, his critique of society, his poetic journalism, his lifelong faith that words matter. He showed us that truth lies not only in what happened, but in how it is felt. Writing, in his vision, was not the transcription of fact but the breathing of human presence.

And thus, Kaleem Omar remains: poet, journalist, companion, witness. His life, like his work, was always song—sometimes unfinished, but always resounding.

The Unchanging Presence: KO's Character and Daily Habits

His humour was large, expansive as the man himself. To intimates, he was 'KO': rough-hewn, genial, a creature of edges softened by the warmth of chai forever steaming at his elbow. He delighted in banter as others delight in music; he savoured the revealing scandal of politics or the crisp record of yesterday's cricket with a relish touched always by seriousness. For the jester's mask never quite obscured the poet's gaze. He dwelt among yellowed newspapers, in a haze of cigarette smoke, while the clatter of typewriter keys served as his metronome. He was no recluse: rather, a presence, vivid and memorable. One encountered him everywhere, at literary gatherings where words rose and curled like incense; at dinners alive with disputation; in newsrooms whose cacophony became his natural element; and sometimes, simply, in silence, his expression half-quizzical, half-melancholic, as though listening to some inner orchestra.

The Enduring Legacy: Memory as Monument

But silence was never his destiny. In the obituaries and anecdotes he endured: the affectionate 'bhai, chai pilao'; the ceaseless clatter of his machine; the curling smoke punctuating a newsroom sentence; his fondness for the dramatic and the commonplace alike. Piece by Piece of My Life, Dawn's tribute, evoked him as one who never wearied of living, whose pursuit of words was a form of breath itself.

His legacy belongs with those who made English poetry in Pakistan not an act of mimicry but of invention. Into foreign metres and alien cadences, he breathed the air of the subcontinent, its soil and fruit, its grief and longing, its politics and passion. His name stands with the builders of tradition, those who transformed experiment into inheritance.

Beyond Literature: The Complete Man

And yet, he was never only a poet or columnist. He was family too, kin to Irfan Husain, Ahmed Rashid, Zeenat Ziad, though always he trod his own solitary road, uneasy with privilege, haunted by memory, restless with exile. His private and public selves interwove: the dinner-table conversation as rich as his printed column; the personal regret folded into his critique of the state.

The Troubadour's Complete Vision

In truth, his life was the troubadour's life. He wandered with poems in his pocket, with columns in the morning paper, with Lucknow's dust still upon his shoes, Lahore's tomes under his arm, Karachi's sea-wind filling his lungs. He lived in the narrow space between longing and satire, elegy and critique. That his great final poem was left unfinished seems but fitting: his life itself remained a work in progress, perpetually incomplete, forever seeking, yearning.

What Abides: The Immortal Voice

What abides is the voice. Robust, lyrical, edged with wit, it continues in memory. The smaller gestures remain: the mentor recalled, the book pressed into a friend's hand, the lament murmured at a death, the dawn celebrated in print. And the larger: his critique of society, his faith in poetic journalism, his conviction that words still matter. He taught us that truth is not merely what occurred, but what it felt like. Writing, for him, was no dry transcript but a human presence made articulate.

Thus, Kaleem Omar remains a poet, journalist, companion, and witness. His life, like his art, was music: sometimes incomplete, sometimes discordant, yet always resounding. To remember Kaleem Omar is not only to honour a journalist and poet; it is to honour memory itself, the tug of recollection, the small light filtering through a crack in the wall, the single spare line that cradles an entire ache. Perhaps this is his truest bequest: that, in the shape of poems and columns, one more voice arose—not to flatter or varnish, but to testify, to register what was, what lingers, what lives beyond vanishing.

Living Twice: The Phenomenon of Literary Immortality

Some men seem to live twice. Once in the ordinary passage of their allotted span, with their cigarettes and newspapers, their deadlines and unpaid cheques, and then again, after departure, in the cadences of their words which cling to air long after the voice has stilled. Kaleem Omar was such a man. Poet, journalist, raconteur, investigator, chronicler of silences, he traversed the latter half of Pakistan's twentieth century as one who belonged both to its centre and its margins.

He could vanish into Karachi's fog one night, only to re-emerge the next morning in print with a column that scorned hypocrisy, mocked pomposity, or stitched scattered fragments of a world into a single luminous thread. For more than thirty years, his byline was reassurance, that one voice remained incorruptible, at once satirical and sorrowful, unafraid to lift a mirror before both society and the self.

The Poet Emerges: Literary Anthologies and Recognition

If journalism was his bread, poetry was his sacrament. His verses inhabit anthologies that map the very genealogy of English poetry in Pakistan: Pieces of Eight (1971), Wordfall: Three Pakistani Poets (1975), A Dragonfly in the Sun (1997). His poetry carried the breath of memory and loss, yet also of humour, play, and gentle rebellion.

Take Trout, from Wordfall. At first glance, it is no more than a fisherman's vignette:

By first light, we are at the river's edge,

unsnarling tackle. Hands with a new day's life in them,

Choose your favourite spoons and pocket sweets

for the thirst that will come to them.

The ritual of dawn, the companionship of rod and river: such is the opening. But then the note shifts, revealing a subtler dread—the fear of humiliation, of falling short before one's peers:

Will I be the only one

Who doesn't have to lie

about the fish I caught?

What begins as boyish anxiety becomes an emblem for adulthood itself, that perennial human unease at being left behind. Omar was a master of such transformations: from the trivial to the universal, from the spoon to the abyss. In Poem for My Father, his register alters, slipping into grief and reverence:

I remember how we would sit quietly, hour after hour,

and listen to your plans.

His father died when Kaleem was young; the absence became an unhealed seam through his work. Where lesser poets might have lapsed into lament, Omar leaned into silence, allowing memory to breathe, permitting restraint to shoulder the weight.

Journalistic Excellence: The Range and Depth of Coverage

If poetry provided cadence, journalism provided a stage. His career was outstanding. The range was astonishing. One week, he might dissect an IMF report with forensic precision; the next, he would recall Fazal Mehmood's 12 wickets at The Oval in 1954, which he had himself witnessed as a young man in England. He always tethered the institutional to the human, the statistic to lived experience.

Colleagues recall him as meticulous yet maddening: forever late with deadlines, yet never careless in craft. He demanded centre spreads, teased his editors with stubbornness, and charmed his readers with prose that mingled satire and lyricism. His obituary of the actor Telly Savalas was so moving that it reached the widow herself. His cricket essays glitter still with anecdote, wit, and a historian's authority.

The Condition of Exile: Geographic and Existential Displacement

But beneath both poems and prose lay the condition of exile. Partition, dislocation, the sundering of East Pakistan—all left their shadows. Though he wrote in English, his ear was tuned to the cadences of Urdu and Persian. Though Karachi was his home, his imagination roamed Lucknow, London, and Dhaka. This exile was not solely geographical but existential: a sense of standing always at the threshold, half within, half without.

The sense saturates his great unfinished work, A Troubadour's Life. At his death, it extended to three hundred fragments, each a shard of memory, each reaching forward to the next. Its very incompleteness feels emblematic. Here was a man forever revising, adding, as though aware that memory cannot be caged, that exile cannot be concluded. He even updated his own obituary annually, as though wary that death might surprise him unprepared, as though words themselves might delay the inevitable.

Piece by piece of my life, he once wrote,

I consign to the page,

not to be remembered,

but to be less forgotten.

The Art of Cadence: Journalism as Poetry

What made Kaleem Omar singular was not just the vastness of his subject matter, but the manner in which it was borne to the page. His prose was not prose alone; it was poetry in disguise, romantic yet disciplined, evocative yet anchored by fact. He did not rant, he reasoned. He did not thunder, he insinuated. His humour, dry as desert winds; his satire, sharp as a surgeon's scalpel; his grief, understated to the point of majesty.

Rare in journalism, he possessed cadence, that subtle rhythm that turns a sentence into song. He restored to reportage the lost dignity of music. As Cardus once clothed cricket's statistics in lyricism, Omar too made fact luminous without trespass upon truth. He understood that journalism, if it is to endure, must carry within it a trace of melody.

The Defining Creed: Feeling Over Facts

"Numbers tell us what happened. Only narrative can tell us what it felt like."

This maxim, which he often borrowed, reshaped, and returned as his own credo, may well stand as his epitaph. For it was the creed that defined him: not the sterile ledger of events, but their atmosphere, their tremor, their lingering aftertaste. His death was mourned not only by family and friends, but by a generation of readers who had come to lean on his presence as one leans on a steady lamp in a flickering night.

The Final Tribute: A Voice Beyond Vanishing

Tributes poured forth, recalling his laughter at the teacup, his loyalty in friendship, his memory that bordered on the encyclopaedic, and his mentorship of younger voices. Yet as with all true writers, he did not vanish. His poems remain, pressed like wildflowers into anthologies. His columns endure, yellowing in the archives yet fresh in wit, still pricking pomposity, still coaxing laughter. His library survives, a bastion of sentences. And even his unfinished Troubadour's Life continues to echo, fragmentary, but perhaps more moving in incompletion than any polished whole.

To read Kaleem Omar is to hear again the hesitant quaver of a batsman's voice before he walks out into sunlight; the laughter of friends gathered by a river's edge at dawn; the quiet grief of a son remembering his father's plans; the restless interrogation of a journalist as he sat among power's evasions. He remains, even now, not only an archivist but also a witness. And in witness lies his immortality. His voice, though stilled, continues to reverberate, not as an echo but as a presence, part of the living atmosphere of literature, a note still held in the air long after the instrument has been laid down.

Dr. Nauman Niaz is a civil award winner (Tamagha-i-Imtiaz) in Sports Broadcasting & Journalism, and is the sports editor at JournalismPakistan.com. He is a regular cricket correspondent, having covered 54 tours and three ICC World Cups, and having written over 3500 articles. He has authored 15 books and is the official historian of Pakistan Cricket (Fluctuating Fortunes IV Volumes - 2005). His signature show, Game On Hai, has been the highest in ratings and acclaim

Dive Deeper

From Pakistan Times to Google News: The story of journalism’s digital transformation

October 26, 2025:

A veteran journalist reflects on the decline of newspapers, the rise of digital news, and how technology forever changed the rhythm and rituals of journalism.

Inside the editorial reforms that changed Pakistani broadcast journalism

April 28, 2022:

Muhammad Ibrahim Raja’s ethical reforms transformed Pakistani television journalism, protecting victims, ensuring safety, and promoting accountability across newsrooms.

Honoring Razia Bhatti: The fearless editor who challenged Pakistan's power elite

August 15, 2025:

Remembering Razia Bhatti, the fearless Pakistani journalist and Newsline founder who died at 52 fighting for press freedom. Her legacy of courage in journalism continues to inspire media professionals worldwide.

From newsroom to UN: Dr. Maleeha Lodhi's historic journey as Pakistan's first woman diplomatic pioneer

August 14, 2025:

Discover the remarkable journey of Dr. Maleeha Lodhi, Pakistan's pioneering diplomat who broke barriers as Asia's first woman newspaper editor and served as ambassador to the US and UN Permanent Representative.

Puppet Press: How Pakistan's media sold its soul to the highest bidder

March 24, 2025:

Explore the 10 critical reasons why Pakistan's legacy media continues to disappoint, from political bias and corporate influence to digital transition failures and unsustainable business models in Pakistani journalism.

Recycled guests and repeated narratives: The talk show problem in Pakistan

September 07, 2024:

Pakistani media is under fire for its lack of investigative reporting, political influence, and censorship. With talk shows becoming monotonous and biased, the public is turning to digital platforms for real news. Read on to learn how Pakistani journalism is failing its people.

Censorship and career: Working as a journalist in the UAE

July 11, 2024:

Explore the challenges and opportunities expat journalists face in the UAE, with insights from Imran Naeem Ahmad, a former Gulf News journalist. Discover the impact of censorship, career prospects, and the reality of working for leading newspapers like Khaleej Times and Gulf News in Dubai.

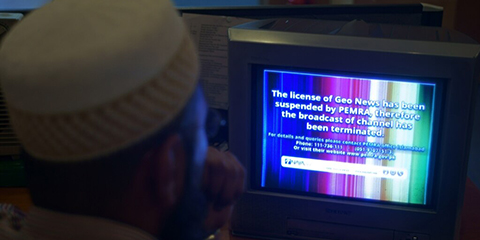

The invisible hand: How censorship shapes Pakistani journalism today

July 09, 2024:

Explore the profound impact of censorship on Pakistani journalism. Delve into the challenges faced by journalists, the erosion of press freedom, and broader societal implications in a country grappling with media restrictions and government control.